Building a serverless MUD infrastructure in Azure

If you went to college back in the 1980’s or 90’s and studied computer science, then it is likely you bumped into the MUD (multi-user dungeon) craze. Back then, computer science was different. The primary languages were the languages of the day - Pascal and C were big. We had access to UNIX systems and would write text-based multi-user games that users would telnet into to get access. We didn’t have the web back then. I learned a lot from writing a MUD - from parser design to network communication. MUDs gave me a life-long passion for programming languages and coding.

The entire system ran from disk on one machine and in one process. We didn’t worry about scaling.

When you connected to the MUD, you were asked for a username and password. In the better systems, passwords were encrypted using crypt(3c), but most just stored them in a file on disk, one per user. We didn’t worry about security.

When we needed to fix things in production, we did it in production - a kill {PID} command would gracefully shut down the service, kicking everyone off the service at the same time. Then we would simply start a new process with the new code. We didn’t worry about down time.

Of course, one can spin up a Linux container and compile the same code that was used back then. We didn’t worry about licensing, but most of them are open-sourced now. But that got me thinking - what would it take to build a MUD today? I don’t mean the code (although I will be thinking about the code in future installments) - but what about the infrastructure? How would I make a web-accessible service that is scalable, secure, and cheap?

What goes into a cloud-based MUD?

When I’m thinking about any new application, it helps to break it down into modules that I can think about. So, what’s in a MUD? In essence, it is a client-server application where the client is relatively dumb and the backend server does all the processing. The complication is that I need to send and receive real-time commands from the server in addition to the more normal request-response type communication from the client. The application can be either a single-page application (SPA) or a server-based (MVC) based application. I lean towards a SPA because then I can write additional types of applications (like mobile apps) that use the same backend.

On the backend side, there are three types of data - static information (like the descriptions of the rooms), dynamic data that is not persisted (like whether a door is open or not), and dynamic data that is persisted (like the score that a player has accumulated). If I have multiple nodes, then all three types of data needs to be the same on all nodes. In addition to command processing, there are also jobs - non-player characters that need to move around and in-game weather changes, for example.

For security, I’ll need some mechanism by which a user can log in and I’d rather it be “someone else’s problem” for security identity information. There really is no reason to be writing your own identity server these days. Microsoft, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Apple, LinkedIn, GitHub, and others all produce a social media identity server you can use. There are also consolidators like Okta and Auth0 that you can use to simplify running multiple identity providers.

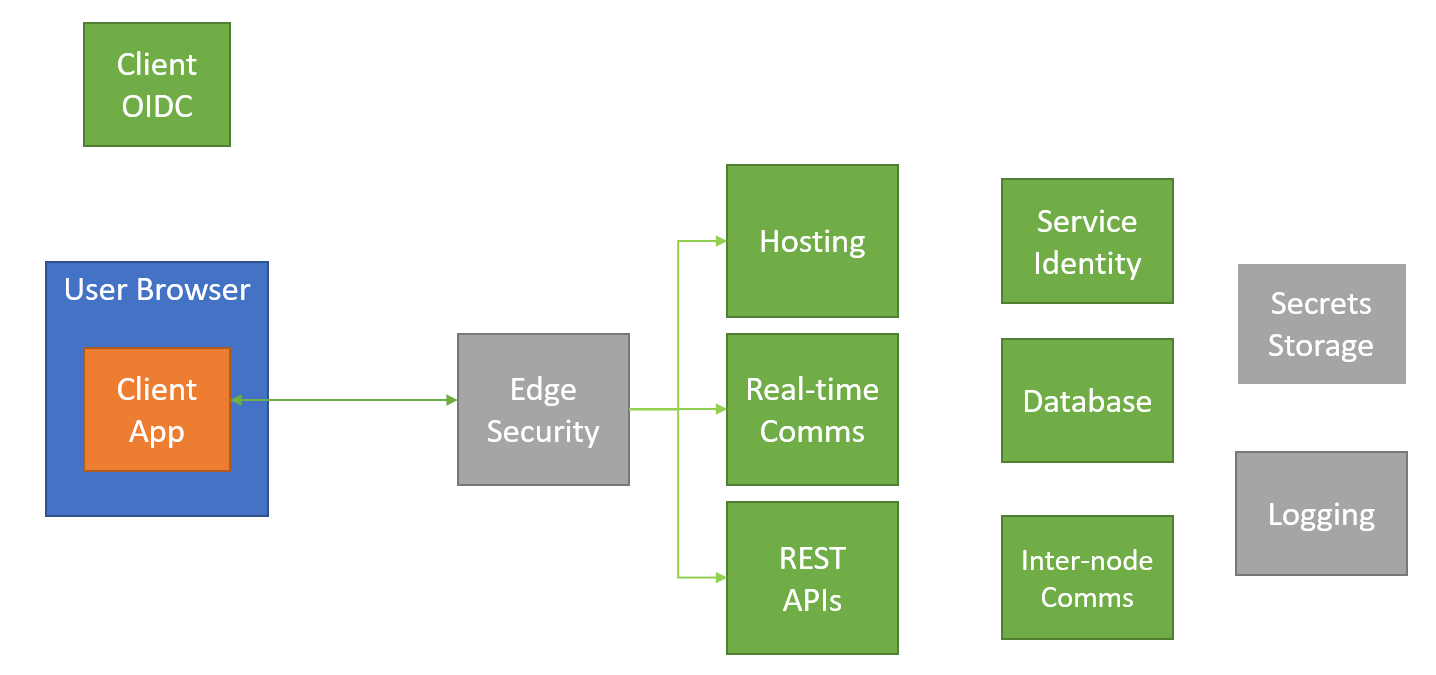

Finally, there are things “around the edge” that I’ll need to think about - Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) protection, logging and monitoring, and securing secrets all come to mind. This gives us a blocky-type diagram like this:

There are a lot of decisions to make here, so let’s get to it!

Single-page application or server-based application?

This is a big one that will affect the options you can choose later on. Once cached, SPAs have faster loading times and can appear to be more responsive to users, especially in low bandwidth scenarios. With the plethora of tools available in modern browsers, they are easier to debug. It’s also easier to build additional experiences like mobile apps. However, SPAs do come with some drawbacks. The initial load of the code is longer (and SPAs are notorious for “code bloat” that doesn’t exist in server-side rendered applications). Finally, there is a problem with caching - your application will not be available after being updated until some time after release, and how long is hard to determine. Server-=based applications, on the other hand, tend to be less responsive to users because every single request is a round-trip to the server. You end up writing more server-side code to support mobile apps as well. However, they load quickly because only the parts necessary to render the page are loaded and you can turn caching off for the code sections, allowing you to quickly update the code when there is a problem and be assured that users are using the new codebase.

None of this determines what language you use to write your app. The two most common languages are C# and TypeScript for large codebases. For a single-page application, you can learn the framework of choice - React, Angular, Vue, Svelte, or Blazor (depending on your preferences). It will all be compiled into a single codebase that can be loaded into the browser from any suitable hosting service. For server-based applications, you can look at Next.js, Nuxt.js, Express, Meteor, or ASP.NET Core with Razor Pages. If you choose a single-page application, you will also need to have an API service for running the server-side code, but it can be much more light weight (and again, there are options available).

Overall, I prefer single-page applications as they provide me flexibility in hosting options and the costs can be significantly lower.

Azure Services

The next step is to consider services that allow me to deliver the front end code to my users so they can run it in their browser and run the service. Since I’m an Azure user, I will run my entire infrastructure inside Azure.

For identity, I’m going to use Azure Active Directory to allow any Microsoft account access to the service. For this, I need multiple identities - one for the client and one for each backend service. Each backend service will have an API exposed and will provide permissions for the client application to access it.

For front-end code hosting:

- I can include a “static files” section in my API server and host the files together with the APIs. I like this option in development as it means I can run the app on my local dev box without worrying.

- Static Web Apps allows me to publish direct from GitHub (no publish step required) and provides automated content geo-distribution via CDN.

- Blob Storage provides a storage container exposed as a web site. Upload the site to the storage container and access it on the web - simple, but no bells and whistles.

For backend APIs, there are a bunch of options:

- Azure Functions provides the serverless option. It is priced per function run (e.g. an API call) and there are time limits on each API call, plus a start up time. This option pairs well with Static Web Apps. I can combine the web hosting with the functions for a single deployment model.

- Azure Container Apps provides a scale-to-zero container compute model.

- Azure App Service also allows you to run containers, but with dedicated hosting. This is designed for web hosting in mind, so there are a bunch of value-added services to take advantage of.

- Azure App Service also allows you to run the web API without containers, again with a mind to web hosting.

- Azure Kubernetes Service is a more traditional Kubernetes cluster management - probably overkill for this project.

Given both the frontend and backend requirements, I’m going to write this as a container and run it on Azure Container Apps. This gives me a great dev box debugging experience, and allows me to easily and cheaply deploy both the backend and frontend at the same time.

For real-time communications, there are two services:

- Web PubSub is a WebSocket transport.

- SignalR Service is a SignalR transport.

Both services do the job - connecting your client apps to the service backend and handling real-time communication. Both can handle embedded authentication and both can handle group messaging as well as broadcasts and individual messages. They both cost about the same, although they have different pricing styles (Web PubSub is priced by the KiB of outbound traffic whereas SignalR Service is priced per message). So it’s really a toss up as to which to use. In terms of ecosystem, SignalR is more aligned eith ASP.NET Core (Blazor Server uses SignalR underneath for communication), whereas WebSockets are more aligned with JavaScript. However, both protocols can be used from both frameworks.

You could also replicate the SignalR or Web PubSub service by linking nodes to a pub/sub facility (like that provided by Redis Cache or DAPR, used inside Azure Container Apps) - but it’s already been done for you, so you might as well take advantage.

You may think you can save some money by implementing the pub/sub through Redis Cache. Actually, all you are doing is shifting the cost - the operational cost may go down slightly, but the maintenance costs go up significantly.

Having considered all the compute needs, let’s talk about databases. I have three types of data, but they can all be run inside of a NoSQL database if I wish. I point all copies of my nodes to the same Cosmos DB and I’m done. However, there are some more potential design choices. For example, I could store the static data as JSON blobs in storage instead, caching them with an in-memory cache on each node. This would be cheaper than Cosmos DB for that data. I could also cache the static data from Cosmos DB in the same way, so it’s not as much a win as you would think. When it comes to dynamic data, however, transaction costs can kill you. I need to store the player data persistently, so that is going into some sort of database - there is Azure SQL, PostgreSQL, and MySQL options as well as Cosmos DB.

The interesting question, however, is what to do with the non-persistent dynamic data. Since I am going to be scaling the containers as needed, there is a probability that I will have multiple nodes, so the data must be synchronized across nodes. I could store that information in Redis Cache (for instance) so I don’t deal with synchronization. I could also use a pub/sub mechanism to ensure the data changes are broadcast to all nodes, which will then hold the state information in memory. This sort of question becomes a cost vs. benefit type of scenario. The cost per transaction goes down at the expense of complexity (and the associated problems such complexity brings).

Initially, I’m going to just use a Cosmos DB connection. If it becomes a problem (in terms of cost or latency), then I will have an abstracted data store that I can adjust to correct the situation.

Finally, let’s think about what are the surrounding pieces I need?

- Azure Key Vault let’s me store secrets securely. A cheaper alternative is Azure App Configuration but doesn’t come with the security guarantees. Key Vault integrates into more services, so I’ll use that here.

- Azure Monitor provide the centralized logging and monitoring. You likely know the log analytics part of this service as Azure App Insights. I’ll also be using some other functionality inside Azure Monitor for tracing, alerting, and container insights.

- Cost Management allows you to set up a budget for the application and notify you when it goes close to or over budget. This ensures that you never run an application that gets too expensive.

- Azure API Management provides API type policy management, allowing you to early reject requests and provide API keys for your individual applications.

- Azure Front Door is a modern cloud CDN that provides web application firewall (WAF) and robust DDoS protection.

- GitHub provides source code control, issue management, and build/release pipelines, allowing me to use CI/CD on my platform for a hands-off safe deployment.

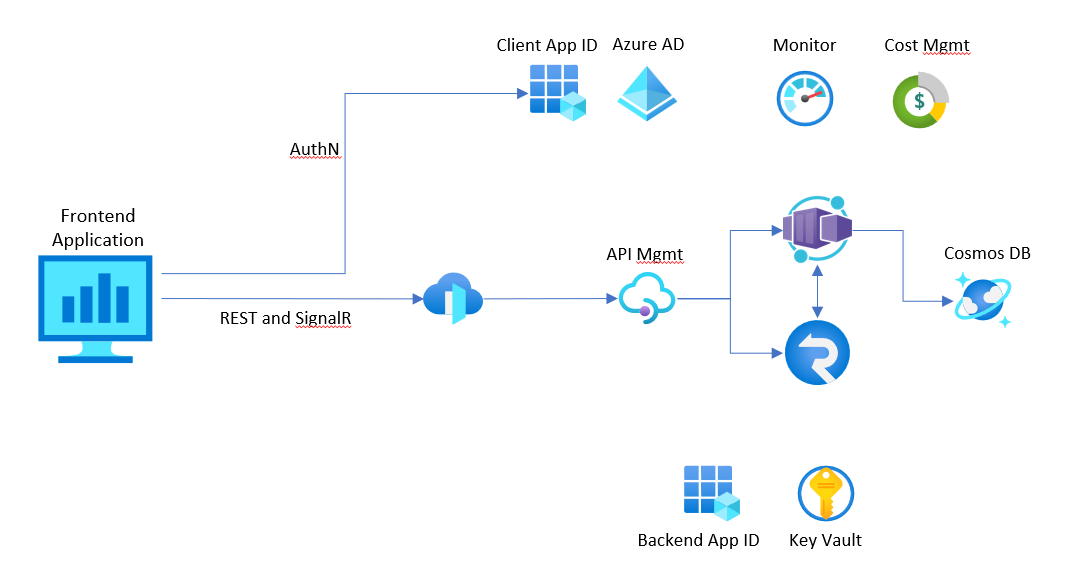

This makes the final design look like this:

What’s it going to cost?

Inevitably, cost comes into any design. I could have made this architecture really cheap - Static Web Apps, Functions, SignalR Service, and Table Storage making up the main components. However, this would have compromised on user experience (in the form of start-up cost), resilience, and testability. The development experience would also be much worse as a lot of the real-time aspects could only be developed in the cloud, resulting in a slower “inner-loop”. The cost would be less than $2/month, however. If I’m into saving money, that may be worth it.

When developing, there tends to be two “loops” that the developer goes through - the “inner loop” is when the developer is sitting at their dev box and using an IDE for coding, building, debugging, and testing. The “outer loop” is when the developer deploys to the cloud for further testing. The “outer loop” takes much longer. Developer productivity is achieved by getting the developer to spend as much time in the inner loop as possible.

To get an appropriate pricing, I needed to make some assumptions about the usage. For example, I thought about “what if 10,000 users played the game consistently?” - I am likely to see about 5-6 REST API calls per user per day, which makes it about 1.5M calls per month (10K x 30 days x 5 requests). There is likely to be many more messages going over the SignalR service though. So here is the breakdown (all pricing based on Central US and Pay as you go):

| Service | Scale | Cost per month |

| Azure Contains Apps | 2M requests | $0.00 |

| Cosmos DB (Serverless) | 3M RUs + 2GB storage | $1.35 |

| SignalR Service | Standard (31M messages) | $49.91 |

| Key Vault | Minimal Usage | $0.03 |

| API Management | Consumption, 2M calls | $37.80 |

| Front Door | Classic, 1 region | $5.00 |

This table was produced with the Azure Pricing Calculator and may not be accurate when you view this blog, in your region, or with your specific subscription. Create your own pricing estimate instead of relying on this information.

Having said that, the infrastructure costs come to less than $100/month for a scalable production data-driven application using containers with both API and real-time communication. The nice thing about scaling with need is that if the customers don’t show up, your price goes down. If you go viral, the price goes up, but you are able to handle the load through the automated scaling.

Next steps

I’m going to start writing my ASP.NET Core and Blazor applications on my dev box and not worry about infrastructure right now. However, once I deploy, I know I’ll be able to deploy changes quickly and scale up quickly to meet demand. You can expect more blog posts as I move forward on this!

Leave a comment